Tuesday, December 30, 2025

Worry-Free Zone

Wednesday, July 16, 2025

Making Your Mark

My wife and I were driving to the airport through downtown

St. Louis and I noticed all the graffiti on a new crosswalk over the

highway. I didn't understand it and most of the time I don't. It's hard for me

to understand why someone would so quickly mar new beautiful construction.

They tell me that graffiti is about self-expression. As if

to say, "I don't have a voice. No one is listening so I'm doing something

out loud here in this art." Sometimes it's marking territory with gangs,

"Just letting you know who is boss around here." Other times it's

flat out rebellion, "You make the rules. I break them. And you can't stop

me!"

At it's fundamental level though, I think it's a way to say, "I was here. Here's the proof." That's why the oldest form of graffiti was usually three words, "Sam was here." "Tracy was here." Hollywood may not know my name, but you will. I'm leaving my mark here so you'll know and you won't forget me.

Remembering Germaine

A few days ago, a woman from our church drew her last

breath, said her last prayer, and closed her eyes for the final time. At her

memorial, stories were shared about her life. Though her body weakened with

age, her zeal for faith only seemed to strengthen. She lived with a faith that

was always visible—never subtle, and she often spoke her mind, but never in a

mean or unkind way.

Often, after Sunday gatherings when I had preached, she would catch me and say, "Shawn, you know what? You're getting better. I'm praying for you and it seems to me that God is on the move around here and He is using you!" I never took offense at the "you're getting better" part, as I am intentional about improvement. I would tell her, "Germaine, thank you for praying. Please, keep it up!"

Paul's Words on Legacy

In 2 Corinthians 3, Paul writes in self-defense, responding

to those "super apostles" who claimed superiority. He asks, "Are

we beginning to commend ourselves again? Or do we need, as some do, letters of

recommendation to you, or from you?" (2 Cor. 3:1, ESV). Paul's point is

clear: he doesn't need a publicist or to in some way leave an obvious mark, nor

does he seek to overshadow others.

Paul continues, "You yourselves are our letter of

recommendation, written on our hearts, to be known and read by all. And you

show that you are a letter from Christ delivered by us, written not with ink

but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets

of human hearts" (2 Cor. 3:2-3, ESV). There is no need to leave behind

physical evidence. You are our graffiti. My legacy is found in

transformed lives—faithfulness and devotion to Jesus are the greatest evidence.

The Mark We Leave

That is the legacy Germaine left for me and for us. The evidence is undeniable. She does not need a plaque in the church, a memorial stone on our campus, or a letter in the paper to mark her life. (Not that those things are bad.) God, by His Spirit, has written graffiti on our hearts: "Germaine was here."

I hope to live in the same way. What kind of graffiti is

your life painting today? Jesus does His best artwork through

the Spirit, painting on the hearts of human beings.

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

WAKE UP TO THE WAR

"The smallest good act today is the

capture of a strategic point from which, a few months later, you may be able to

go on to victories you never dreamed of".

Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis

In my 20’s, I served under a senior pastor who had his share

of war stories. Not so much those about church wars, but what it was like to be

a boy while WW2 was raging. He would tell of scrap metal drives and victory

gardens, of women riveters and uncles coming home permanently dismembered or

never coming home at all. What I heard running underneath his accounts was the

American mindset of the time: “We were in the war together. We saw ourselves united in the struggle.”

Peacetime came and America entered a season of greater

prosperity. Boys came home, houses were built, and babies were born. We’ve had

wars since then, but none would come close to spawning the level of national

unity America experienced during those years.

As Christians, we often fall prey to the peacetime vs

wartime mentality. When things are going well, we may think, “Oh, this is my

breakthrough. The battle is over for now.” When unrest comes or a family faces

opposition within or without, we think, “I guess we’re in another battle.”

This is a faulty mindset. Truth? We are always in a war. In

fact, the battle may be more severe when it seems things are going great. Money

in the bank, numbers up, strong friendships, even momentary euphoria--all of these can make you relax and think, “So these are the good days of blessing.”

Someone remarked recently, “Man, it seems like you guys, the leadership, all get along so well. There's a lot of unity and pride doesn’t seem to be a problem.” I told them it was no accident.

It isn’t just that we have a great team of leaders, which I

think we do. Nor is it that we don’t have any big egos (which we probably do!).

It’s that we get up and fight for what's good. We remind ourselves often that we

are in a protracted war. An insidious force is fighting against us every day; unseen

spirits, angels led by a dark lord, and a world with its agenda, also in league

with my human flesh, are all conspiring against the work of Jesus. These dark

powers are cooperating together to destroy unity, to spout constant

discouragement, to fight for independence against our great God, and to spread

lies about His goodness, faithfulness, and character.

“Sometimes just getting out of bed is a victory.”

When I forget this, I am vulnerable. Every step

toward faithfulness is warfare. Sometimes just getting out of bed is a victory.

The prayers of the saints in the pre-service intercession on a Sunday morning.

The office team prayer at a weekly huddle. The growing of

ourselves in leadership and the acknowledgment of our blind spots. The prayer

circles in the Wednesday prayer meeting when there are voices that say, “This

makes no difference” or, “You’re not very good at prayer. Don’t embarrass

yourself by praying with others.” The prayer before a Celebrate Recovery

meeting. The news I received this morning that a women’s Bible study feels prompted

to begin praying for our children’s camp. News that a man was freed from

demonic oppression in a recovery meeting. When we listen well. When we lay down

our iPhones to read scripture. When we ask a friend for forgiveness, when we

confess our faults. In all these things, we are fighting the good fight. All of

this is a reminder: this is the nature of war.

I’m not being negative. It’s our reality as Christians. And yet in all this, I am encouraged. I remain hopeful. God is with us. Jesus is interceding for us. The Spirit is helping and empowering us. The ultimate victory of Jesus and His kingdom is certain. But get out of bed. Put on your armor. Pick up the sword of the Spirit and keep your eyes open. If you're a Jesus-follower, we’re in this battle together.

"And pray in the Spirit on all occasions with all kinds of prayers and requests. With this in mind, BE ALERT and always keep on praying for all the Lord’s people." (Ephesians 6:18 NIV, empahsis added)

Wednesday, April 03, 2024

Preacher/Teacher: Let's Lose these Words

I'm not a health nut. But people think I am because some of

my favorite foods are salmon, brussels sprouts, and sliced tomatoes. I've been

known to order the "all vegetable" plate at Cracker Barrell, too.

Gasp. This will send some of you because you're saying, "There's nothing

of nutritional value left in those vegetables cooked for 10 hours with bacon

drippings." Exactly. Still, when I enjoy a Boston Creme donut on occasion,

the food police are on the spot to smirk and say, "Wha?? How could

you?"

So this is dangerous. Whenever you offer advice publicly,

beware. People remember and will hold you accountable.

This is why I'm hesitant to warn about words that we

preachers and teachers say. At the same time, I'm writing this in the hope that

it will cure me of some of my bad habits by writing them down in a post.

There's nothing like public warnings to make you more aware of your

faults.

So here goes a short list of words I'm trying to lose from

my public speaking...

1. Use the generic "God" sparingly.

In a pluralist society like ours, you can no longer assume

that when someone is talking about God they are Christian. Any quick Google

search of "famous Christians" will pull up actors and politicians who

quote a verse or say, "I want to thank God for the opportunity to win the

Super Bowl." I hope and pray it’s true. But there are many public figures who pray before an event or thank God for an award who also reject biblical

Christianity. In this day, we need to be clear. I don't mean veins bulging and

stern faces. But we must preach Jesus as the way to God. Jesus as the Son of

God. Jesus as God with skin on. Jesus as the One of whom the Spirit speaks

(John 1:1, 1:14, 14:6, 16:13). Consider John, the beloved friend of Jesus who

says this, "Who is the liar but he who denies that Jesus is the Christ?

This is the antichrist, he who denies the Father and the Son" (1 John

2:22 ESV). This is a solemn warning to we who preach and teach. God help me!

Speak of God, yes. But along the way, make clear that you

are talking about the God revealed in the scriptures, and in the end, the One

who gave His Son to redeem us.

2. Lose "things."

I don't remember the actual source, but I thank H.B. Charles

Jr. for this one. I either read or heard him telling preachers to quit

preaching about "things."

I did this often when I started speaking and still fall into

the trap. It goes like this: "The first thing we notice in this

verse" or, "The first thing we need to do in prayer is..." or,

"I'm going to point out three things Paul says about marriage." Why

use "thing" when there are so many better words to choose from?

Instead of talking about "three things," talk about three ways,

benefits, warnings, threats, guardrails, strengths, weaknesses, attitudes, or

outcomes. Which sounds more interesting as a talk or an article: "Three

things about friendship" or "Three roads to healthy

friendship"?

How much more as we teach or preach the gospel should we use

words that evoke emotion and spark interest? Did God give His Son to simply

give us some tips on having a better life? Or to help my day go smoothly? God

gave His Son so that we can have a relationship with God the Father and align

our human relationships with others. A gospel-shaped friendship is about love and

love is more profound than tips, things, or points. Though it certainly includes

them. Consider Jesus' way of teaching the gospel: two houses, two sons, or a bride and her wedding. Lose boring words

like things, points, tips, or thoughts.

3. "Right? "Alright?" "You

know?"

This is a tough one. Public speaking is much more

conversational than 20 years ago. Overall, I don't see this as a problem.

Styles and rhetoric change and in our culture people prefer conversational over

rhetorical. HOWEVER, I can resort too often to words that have more to do with

my discomfort than with a conversational style. The temptation is to elicit a

response rather than let the statement hang for full effect. This bad habit

frequently reveals itself in our attempts at humor: "So, I'm on a road

trip with my wife and the night before we are both doing that last-minute rush

before leaving. Right? I get no sleep because it's a short night, you know. And

then we're driving and my wife asks if I want her to drive and I think yes or

maybe, but say no because I want to be the self-sacrificing gentleman. Alright? But

then she's snoring and sawing logs, you know, and I'm soon driving on those

bumps on the side of the road to wake her up because I'm jealous. Right?"

For a different way to tell a humorous bit, consider how

Nate Bargatze lets funny statements hang without constant solicitation for

response. (Here's an example in

a story about a horse. Watch from about 2:35-5:33.) Or

consider the serious expositor, David Platt, who uses humor without the filler

words of "alright" or "right." (Watch this clip from

about 8:15-9:15.)

4. The ambiguous adverbs: actually, literally,

really and just.

One of the longest short flights I ever had was sitting

beside two high-school or college-age girls while preparing a message for the

weekend. Even with headphones on, I found myself counting the words 'like' and

'really' in their conversation. I lost count after 40. I couldn't concentrate

after a while and instead started counting the minutes before we could land and

I could escape. It was awful.

So go the ambiguous adverbs: actually, literally, really, and just. What do these words ACTUALLY mean? I'm not sure, but I use them all the time and they aren't helpful. It's a hard habit to break because these filler adverbs leak into our conversations and public speaking to promote a more casual feel.

And the deeper reality? I fight insecurity and the pain that

comes with it because of my great need for the gospel. If I believe the gospel

deeply, I will lose some of my fears of silence, pregnant pauses, and the need to fill in

the gaps for God.

Yes, adverbs are necessary, but they are like salt: a little goes a long way. I am actually one of the worst offenders and I really need to break this habit. (Smile.)

There are many more useless words I use in my speaking. But

here's my stab at getting better. How about you? What words in conversation or

public speaking distract you?

Tuesday, January 16, 2024

WE'RE MORE ALIKE THAN WE ARE DIFFERENT

This flies in the face of current thought. We think we are completely our own. Our identity is self-determined. Culture says, 'If you don't like who you are, look within. Find who you want to be. Reinvent yourself. The power is inside you.'

Some have found this to be exhausting. The weight of self-discovery is unbearable if I'm the only one worthy to decide my identity. If we are merely atoms randomly held together by scientific laws, who I am to then take this brain given to me by the universe and figure out who I am and why I'm here?

Kapic speaks to this:

“Any attempt to live as my own center shows that I need others to understand myself and I need them even more to be a healthy and thriving human creature. This is how God made us. Because we have our being in relation and not apart from it, knowing one’s self rightly can only occur in the context of being known, of being in relationships, of being loved. The self alone, the isolated ego, is a contradiction in terms. Pursuing that contradiction leads not to life-giving knowledge but to suffocating loneliness and unending self-doubt.”

I think he's right. Do you?

For example, I used to think that small groups were for those lonely people out there. "Pastors like me, don't need to be in a small group with ordinary people. Maybe a group of pastors or high-level leaders would be better?” How wrong I was! My self-view was so distorted by looking within and seeing myself as a leader who should be around other "leaders” that I was overlooking my sameness.

Instead, what I've found is that being around other people with different interests and vocations than my own has brought me joy. It's pride that makes us think, "I'm not like other people. I'm unique." Yes, there are some unique things about me. But I'm more like everyone else than I'm not. And you are too! We all get tired, sleepy, restless, hungry, and even dare I say, gassy?! You're not that unique.

Occasionally in our church, we will get a request from someone new that goes something like this: "Do you have any small groups with people my age who are urban professionals? I'm also interested in clean-earth policies and want to be around people who share that view. It would be nice, too, if there were other vegans in the group--since I have strong feelings about eating things that have eyes."

Okay. So I'm exaggerating. But only a little.

I want to ask them as well as you, what might you discover about the world and yourself by being in a group of human beings--some who will share your likes but others who will see the world differently? You may find that the human condition is universal---that you are more like those "other people" than you think you are. Here's what I know for certain: if you dive into the risky adventure of knowing other human beings and being known, you will get hurt. You may get angry. But you will also likely discover what it's like to be loved and to escape the chronic loneliness of this divided world.

"We are not self-made people, we are not separate islands, we are not merely rugged individuals. Instead, we’re inevitably and necessarily bound together with others: it has been so from the beginning and will always be." (Kelly M. Kapic)

Go to a church where other human beings are. Find a group of other human beings who want to know God and each other. Do life. Your identity will reveal itself in the context of community. Not without it.

Monday, January 01, 2024

My Top Books of 2023

There are great lists out there from much brighter minds than mine, for sure. But I do like to share books that have helped me. Since I am receiving input on a constant basis from media and God’s enemy, I need to counter that messaging. Also, reading is simply good for the mind rather than being passively entertained.

So here goes!

These are in no particular order of importance but culled from the 30 or so I read this year.

ON GETTING OUT OF BED BY ALAN NOBLE. Vulnerable and helpful. I recommend this for anyone who deals with mental illness and anxiety or loves those who do. Alan is a professor at OBU and he makes clear that he is not a mental health professional. However, he comes alongside as a helpful fellow-traveler. It’s also a short read at just over 100 pages which is a bonus!

WHY THE REFORMATION STILL MATTERS BY MICHAEL REEVES. I’ve read several by Reeves and no disappointments here for me. St Louis is often called the Rome of the West with its strong Catholic presence. Hence, I am frequently interested in understanding both the Catholic tradition and the Reformation for the purpose of dialogue with my Catholic friends. Even though evangelicals have much common ground with Catholics, Reeves shows why the Reformation was and is still a big deal. He writes convincingly, yet not arrogantly. I also love hearing his knowledge of church history.

RUN WITH THE HORSES BY EUGENE PETERSON I like to read a couple of commentaries on books of the Bible every year and I chose this one because a friend of mine said he “cried nearing the end because he hated to see it come to a close.” While I didn't share that strong emotion, I was frequently moved as Peterson walked through Jeremiah, showing him to be a real man who often felt inadequate for the mission. I felt like I met a new friend in this OT prophet and it was a big help in our series on Jeremiah in 2023.

HUDSON TAYLOR’S SPIRITUAL SECRET BY F. HOWARD TAYLOR. I try to read at least one biography of a dead missionary every year and while I’ve read about Taylor before, this one was the best. If you want your faith to grow, check this out. The ways that Hudson trusted in God as a missionary and saw countless answers to prayer will inspire you.

STRANGE NEW WORLD BY CARL TRUEMAN. Trueman is one of the best at understanding this cultural moment as well as discovering ways of engaging it. His writing is a bit heady but this one is shorter and more accessible than some of his other works.

ON THE EDGE OF THE DARK SEA OF DARKNESS BY ANDREW PETERSON. One of our pastors reads this series to his son, and I kept hearing about it from different men. It’s a juvenile work but I chose it to give my mind a break while reading Carl Trueman’s “Strange New World.” I wasn’t disappointed and loved the ending. I highly recommend this for reading with children above the age of 7 or so but even for you adults who like me just need an easy book to read that will raise your hope in dark times.

Honorable mention:

Gospel: Recovering the Power that made Christianity Revolutionary by JD Greear

Unmasking Male Depression by Archibald Hart

Identity Theft by Melissa Kruger and others

The Trellis and the Vine by Colin Marshall

Pride: Identity and the Worship of Self by Matthew Roberts

To better reading in 2024!

~Shawn

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

PREFERENCES: When Christians Disagree

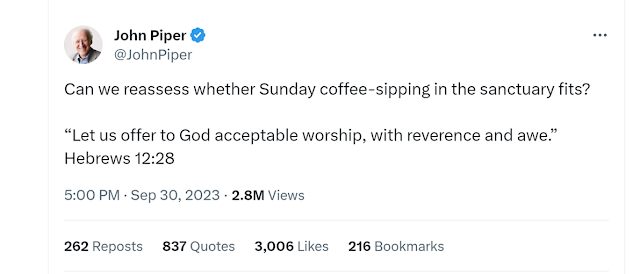

Respected pastor and author, John Piper, caused a minor firestorm when he posted a question about whether sipping coffee and reverent worship go together. You know you’ve touched a nerve when something like this goes viral:

As of today, it’s been viewed nearly 3 million times[i] with 3,000+ likes. And I

have to admit something about his question resonates with me. But I’ve been

examining my own heart.

When my wife and I prepare couples for marriage, we begin a

conversation about expectations. Right or wrong, good or bad, every couple

bring expectations into their relationship. These are largely based on experience,

often from their family of origin. We don’t tend to think about these

expectations because everybody thinks their normal is normal. (i.e. The guy

works on things that break down and the wife does most of the housework.) The

sooner you can identify those expectations and talk through them, the better.

These stereotypes can be the source of strain in a marriage:

“I just assumed she had the accounting under control.”

“My Dad was super handy around the house, so I expected

my husband to do the same.”

These expectations don’t have to be a problem if you discuss

them in advance and identify what is an absolute and what is a preference.

The same thing is true in spiritual matters.

If you have no spiritual heritage, there aren’t many

expectations. Not much to compare to except bad flicks and sitcoms. But if you

do, these expectations can turn into heated arguments that divide friendships

and churches. The sad part is when we can’t discuss them in a reasonable way.

“The pastor should visit me in the hospital.”

“Everyone on the platform should wear business casual

dress.”

“It is irreverent to wear flip-flops while preaching.”

“Suits and robes symbolize false superiority.”

“Church is not a building. Worship is more authentic outdoors.”

What comes up when we read these statements is related to

our beliefs, expectations, assumptions, and experiences. What is hard for all

of us is to discern when something is simply a preference.

It’s helpful to pull back from the emotion if we can and ask,

“Is my expectation based on my unique experience? Is this a preference or is

this an absolute?”

Some like Erik Thoennes have distinguished between these by

dividing beliefs into categories like absolutes, convictions, opinions, and

questions.

I have tweaked his diagram to look like this:

1. Absolutes - theological truths that are timeless. They are true in every place

and every time. For me, and for orthodox Christians, these are scripturally

clear doctrines.

2. Convictions - beliefs we hold, based upon principles in scripture. They may have

strong implications depending on the culture.

3. Opinions - knotty theological matters that Christians have debated for

centuries. If we’re wise, we don’t divide friendships and fellowship over

these.

4. Preferences - things we prefer. They may be loosely based on scripture, our experiences, or our cultural context.

Let’s take flip-flops for example. One person in a

conservative church in the United States may say:

It’s so disrespectful and irreverent to read scripture or

lead worship in flip-flops.

But scripturally this is impossible to defend as an

absolute. If anything, we could argue the opposite---that we are being more

like Jesus when wearing flip-flops because he wore sandals. This is also

cultural. I have a friend in India, who asked us to take off our shoes before preaching

because they consider the platform to be holy ground. (i.e. Moses took off his

shoes before the burning bush.)

Then there’s the question of whether it’s appropriate for a

minister to wear footwear that cost more than $100 USD. One might argue that

wearing expensive shoes should disqualify one from leadership when it’s

obvious that style or comfort has become more important than gospel ministry.

(i.e. Shouldn’t the money spent on those Carhartt boots have been spent on the

poor or for missionary work?)

What if we could simply admit that many of these are

preferences? Not absolutes. If not preferences, could we at least admit these

are convictions that we hold? Not absolutes?

Some people prefer classical music, organs, handbells and

choirs. Some prefer guitars and exuberant settings. Some think that robes and

suits reflect more reverence. Others see these things as ostentatious or, at

least, pretentious.

Bottom line? The scripture doesn’t prescribe some things for

all places and all times. And we should be careful not to call those things, absolutes.

For example, there is no scriptural mandate that worship

should be done by candlelight, sunlight, or LED lights. We may prefer candles.

Others may be triggered by candles because of association with austerity rather

than simplicity. Others say good lighting helps them to focus on Jesus rather

than the “charismatic waver” in the third row.

Congregations, elders, and leaders should sort out what

communicates reverence within their own cultural context. What symbolizes

reverence in one tradition is irreverent in another. What is sacred space in

one culture is impossible to achieve in a poor neighborhood.

At the same time, we should beware of our fallenness. Pride

is subtle. We are blind to our…blind spots. To truly worship requires dying to

something. Can we say we are truly worshipping if it costs us nothing? Sometimes

what it costs us is our preferences.

Some of the same people who say, “It is irreverent to

worship with flipflops, t-shirts and jeans” are the same ones who say, “I can

get just as much out of worship at home.” They see no problem worshipping at

home in sock feet and bathrobe, eating Rice Krispies or scrolling on their

phone while the minister prays.

Let me be clear. I am not condemning the person who can’t

attend a worship gathering because their body hurts, or they find it dangerous

to walk on an icy parking lot for fear of falling. What I am questioning is how

quickly we divide over our preferences considering them as non-negotiable

absolutes.

Disputable matters

Accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarreling over disputable matters. (Romans 14:1 NIV)

As a pastor for 40+ years, what is sad to me is how often

people divide a congregation over preferences or opinions on disputable matters

and how rare it is for someone to leave over truly theological matters.

It is honorable, although not commanded in every case, to divide

over absolutes or convictions that have strong implications for culture and the

future of the church.

Here are some good reasons to leave a fellowship:

· When the statement of faith is no longer rooted in scripture.

· When the church pivots simply because “we don’t want to offend anybody”

· When the leadership team is more concerned about seeking a crowd than seeking God.

· When the pastor talks more about good behavior than the good news (the gospel)

· When the pastor or elder’s personal life doesn’t match his pulpit life

There are more. But let’s not imitate the popular worldview

that says, “If you disagree with me, you are hateful.”

Let’s also beware of our own pride that slices both ways. Do

we make our preferences holy just because we like them? Are our efforts

to “be authentic” simply an exchange for a different style that we happen to

prefer? Do we sneer at someone who worships in dress shoes as if they are pretentious

or arrogant? God knows the heart. The hipster who wears his sandals can be more

proud than a guy in a suit who straps his guitar too high and still perms his

hair. We can become “proud” of our authenticity.

For those of us who grew up in a Christianity with big screens,

suits and permed hair, it’s easy for us to look at our jeans, candles and

contemplative moments as holy and authentic. But I should beware.

Remember the worshipper Jesus describes who stands and prays, “Thank you, God, I’m not like that guy over there. He’s a sinner but I’m in good-standing with you” (Luke 18:11). This can happen just as easily in jeans as a robe. For some, this happens with a sneer from a lady in the back row who wears a dress and an expensive broach. For others, it’s a snicker as we scroll Instagram and see that guy in a suit singing “Shout to the Lord” in the wrong key. I can be the Pharisee in jeans and Birkenstocks just as easily as I can in a suit and black wing-tipped shoes.

[i]https://twitter.com/JohnPiper/status/1708240310495527147?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1708240310495527147%7Ctwgr%5Ead361f7596f92e43e32377fdc6405e1cc05f44cc%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.premierchristianity.com%2Fopinion%2Fjesus-java-and-john-piper-should-you-drink-coffee-in-church%2F16454.article

.jpg)